Gov. Mike Kehoe hasn’t called a special session but a statement after the president’s social media post indicates he is moving closer to convening lawmakers

BY: RUDI KELLER

Missouri Independent

Missouri “is IN” for redrawing the state’s congressional districts in a special legislative session, President Donald Trump proclaimed Thursday on his social media platform.

With Texas moving quickly toward a mid-decade revision of its congressional map to tilt five districts toward the Republican Party, Missouri would now be expected to follow suit to help the GOP gain one more.

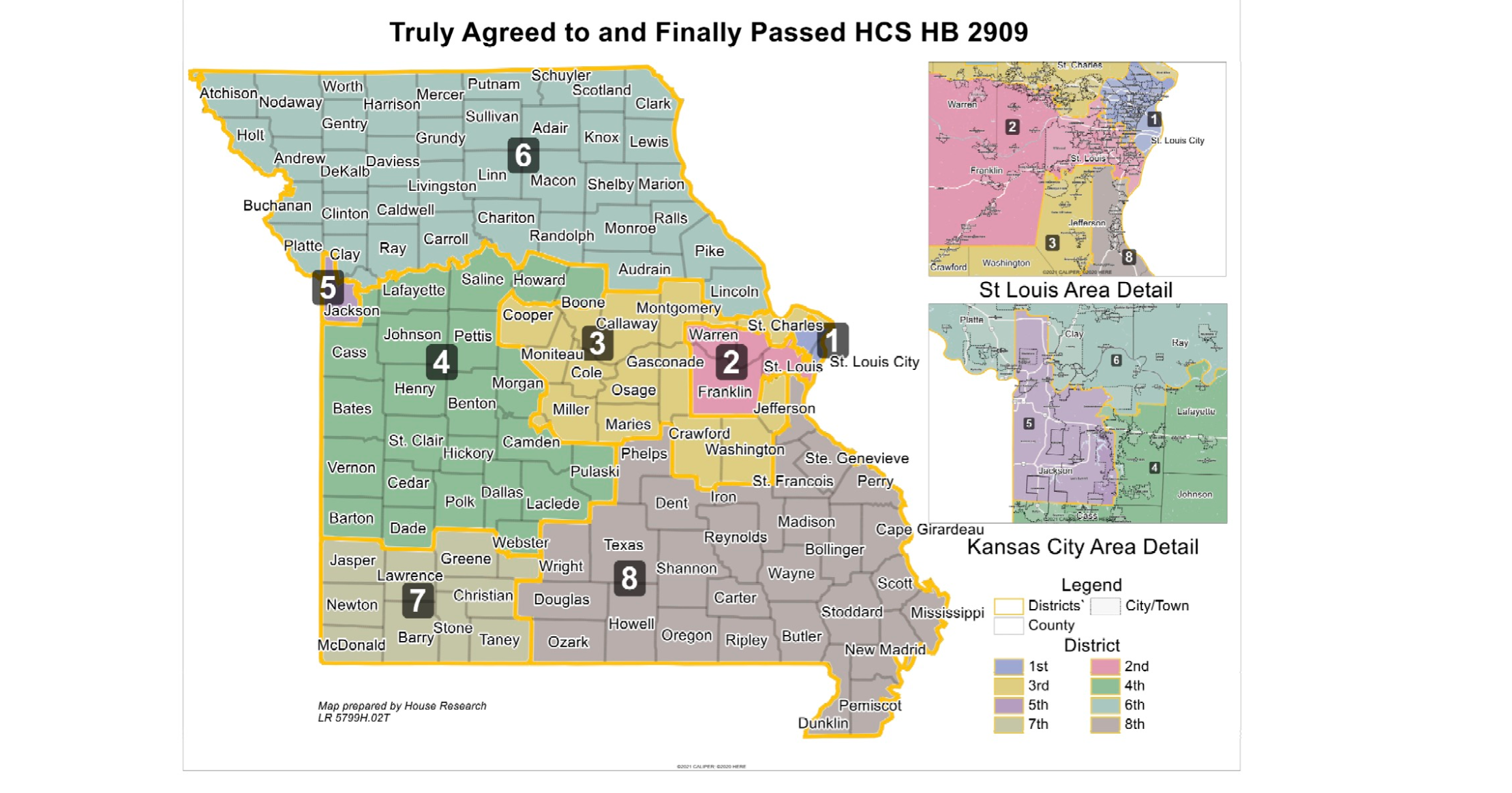

Missouri has eight congressional districts, and Democrats hold two. Any proposal is likely to split the 5th District, which is mainly in Kansas City, by adding Republican voters in sufficient numbers to take it away from incumbent Democratic Rep. Emanuel Cleaver.

That would give Republicans seven of the state’s seats in the U.S. House.

For nearly a month, Trump has been pressuring Gov. Mike Kehoe and legislative leaders, with calls to at least one Republican lawmaker who expressed reluctance to go along.

“The Great State of Missouri is now IN,” Trump wrote. “I’m not surprised. It is a great State with fabulous people. I won it, all 3 times, in a landslide. We’re going to win the Midterms in Missouri again, bigger and better than ever before!”

And Kehoe, in a statement responding to Trump, inched closer to saying he intended to call a special session. At a news conference in his office Tuesday, Kehoe said no decision had been made.

“Governor Kehoe continues to have conversations with House and Senate leadership to assess options for a special session that would allow the General Assembly to provide congressional districts that best represent Missourians,” a statement sent by spokeswoman Gabby Picard read. “Governor Kehoe appreciates President Trump’s attention to this issue on behalf of Missourians.”

No proposed map that would favor Republicans has been revealed, and a top Republican on Wednesday told The Independent she has been unable to get a look at one circulating privately.

“I’ve tried to get a hold of the map that I’ve heard about,” said Jennifer Bukowsky of Columbia, vice chair of the Republican State Committee. “I guess I’m not important enough to be consulted.”

The push for redistricting in Republican-led states is an effort to shore up the thin Republican majority in Congress. With a 219-212 majority — four seats are vacant, including three previously held by Democrats — Republicans are worried that a small shift in voter sentiment could put them again in the minority.

Redistricting is usually done in the first legislative session after census data is released, and the districts remain in place for 10 years.

Missouri’s current congressional map was approved by lawmakers in 2022 after a bitter GOP factional dispute that centered on efforts to draw seven Republican-controlled districts. And with Democrats promising to filibuster any redistricting bill in the Senate, getting a new map approved will also be difficult.

A special session will show that Republicans in Missouri take “marching orders from the federal government,” State Sen. Stephen Webber, a Democrat from Columbia, wrote in a social media post. “Pathetic to watch grown adult ‘leaders’ flop around like caught fish when a New Yorker that thinks the Chiefs play in Kansas tweets at them how to run Missouri.”

When he spoke to reporters on Tuesday, Kehoe said the biggest consideration for him is maintaining the Republican majority in Congress.

“Our goal, if we move forward — and there’s no decision to move forward — is to make sure Missouri’s values are reflected in Washington, D.C.,” Kehoe said. “And I’ve said many times that I think our current speaker does a very good job of matching the values of Missourians.”

Republican members of the Missouri House have been told there will be two caucus meetings scheduled to coincide with the annual veto session, which starts Sept. 10, state Rep. Barry Hovis, a Republican from Cape Girardeau said Wednesday in an interview with The Independent.

One meeting, he said, is presumably to discuss whether there are any vetoes the House wants to override. In the other, Hovis expects an in-depth discussion of redistricting.

For Hovis, one consideration on whether to redraw Missouri’s map will be if Democratic states California, Illinois or New York revise their maps in response to the action in Texas. Gerrymandered districts that give one party far more representation than their share of the overall vote can be seen in every state dominated by a single party, he said. Illinois has a district that looks like a snake, he said, while Massachusetts — where Republicans get about the same share of the vote as Democrats in Missouri — has no GOP congressional seats.

Democrats will complain they are being denied representation, Hovis said.

“If they’re going to bring (Texas) up, I’m going to say, ‘Well, we’re just doing what you guys taught us to do,’” Hovis said.

Until Kehoe makes the call, Hovis said, the whole discussion is speculation.

“For me to tell you that I know exactly what we’re going to do here, I truly don’t,” he said.

The biggest challenge for Republicans, Hovis said, will be to draw a map that doesn’t put districts the party currently holds at risk with large numbers of new Democratic votes.

“If we go to the Kansas City model, the one that I saw when we did this several years ago, we’re going to have some districts that could be more purple than red, and we could end up being 5-3, real easy, or worst case scenario, 4-4.”

The people most interested in redistricting, Bukowsky said, are incumbents. They want a map that retains the voters who have come to know their name, while potential opponents want a map that includes voters who share their ideology.

“Whenever they’re doing redistricting,” Bukowsky said, “it’s like the two parties are incumbents and challengers.”