Patients of NKC Health in North Kansas City finally learned in late November that their data was compromised in ‘one of the most massive breaches in the health care industry’

By:Suzanne King

In January, hackers gained access to a cache of Cerner electronic health records stored on a legacy network.

But some patients whose sensitive health and financial information may have been exposed are only now being notified — and many others still haven’t been told.

NKC Health, formerly North Kansas City Hospital, is one of the most recent hospitals to let patients know about a cyber incident involving Cerner, now Oracle Health. The Nov. 25 notice said the hospital had only “recently learned” of the incident, which has been unraveling for months and reportedly dates back to January.

About a dozen hospitals across the country, including Mosaic Life Care in St. Joseph, Missouri, have sent similar notices to patients. Oracle has not publicly disclosed the number of hospitals involved or how many patients may have been affected.

But Elena A. Belov, a lawyer representing victims of the data breach in a federal class action lawsuit filed in the Western District of Missouri, said she has been told by Oracle’s attorneys that 80 hospitals’ patient records may have been involved. And that could amount to millions of victims.

“This is one of the most massive breaches in the health care industry in the last couple of years,” said Belov, who practices with the Almeida Law Group. “We still don’t know the entire universe. The list of affected hospitals has not been made public.”

Oracle Health, which acquired North Kansas City-based Cerner for $28 billion in 2022, did not reply to requests for comment about the incident. The company is the country’s second-largest electronic medical records vendor, managing patient data for about 20% of the nation’s hospitals and doctors’ offices.

News reports about the January data breach said it involved data on Cerner’s old network that had not yet been transferred to Oracle’s cloud network.

While details of the Cerner data breach began appearing in news reports last spring, and the company started informing customers about the incident this summer, Oracle did not announce it to the media, and left it up to its health care clients to report the breach to patients and to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Civil Rights’ Breach Portal.

“It goes to the big problem we have,” Belov said. “Even huge companies who are in the business of digital security like Oracle are not paying enough attention to security.”

Health care data breaches are common

Data security experts said the Cerner network hack illustrates just how vulnerable patients’ health and financial information can be.

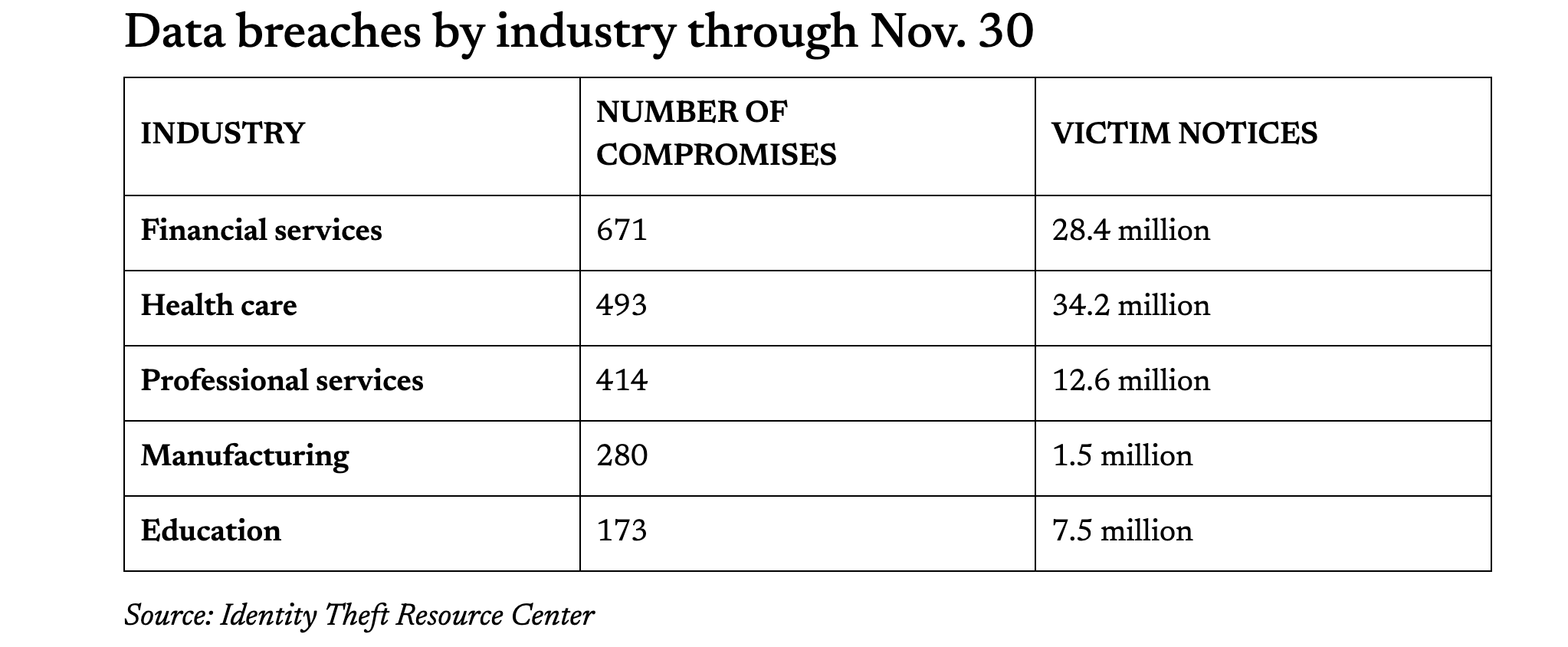

During the first 11 months of 2025, health care organizations reported 493 data compromises, which involved more than 34 million victims, according to the Identity Theft Resource Center, a nonprofit that tracks and works to prevent such incidents.

Until 2024, health care accounted for the most data breaches of any industry for six years in a row. But last year the financial industry took the top spot and health care came in second. The trend continued this year.

James E. Lee, president of the Identity Theft Resource Center, said health care is particularly vulnerable to cyber attackers because it is so large and diverse.

“There are small providers in small towns, all the way to huge multinational health care organizations and everything in between,” he said.

Health care involves hospitals, doctors, pharmacies, labs and insurance companies, all of which have access to patients’ personal information, including identity data like Social Security numbers, names and addresses; financial data like credit card information; and personal health information like diagnoses and medications.

All it takes to break in is one legitimate login and password at one point in the system. That leaves plenty of room for weak links, Lee said.

Companies like Cerner, which digitize health records so every doctor and hospital has easy access to patient charts, have become a major part of the system. From its beginnings in 1979, Cerner’s founders promised the electronic management of health records would cut costs and bring better care.

“The idea of digitizing the records — from a patient perspective — was a good one,” Lee said. “What we didn’t anticipate, and it is true across all industries, is the level to which professional criminals would become engaged. These are professional, multinational organizations, not some kid sitting in a basement drinking Red Bull.”

NKC Health incident

NKC Health’s statement said its patients’ records may have been accessed as early as Jan. 22, but Oracle Health only informed them about the incident recently.

In its notice to patients, NKC said Oracle Health told the hospital that “law enforcement investigators” had urged it to delay notifying patients and hospital customers “because it could have impeded their investigation.”

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), the federal law that deals with patient privacy, requires health care providers and their associates to notify patients when sensitive information has been compromised “without unnecessary delay,” and no later than 60 days after an incident. But the law makes an exception if law enforcement requests a delay.

News organizations reported in March that the FBI was looking into the attack, and in April, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency issued a security alert, warning that “the nature of the reported activity presents potential risk to organizations and individuals.”

Oracle has informed some of its hospital and physician practice customers about the data breach individually.

Belov called the lack of transparency “really dismaying.”

“We’re losing valuable time for people to protect their information and their identities,” she said. “This is going to be a huge problem.”

Stolen data comes with ‘deadly outcomes’

Legal and health experts said breaches of health care information can be among the most concerning.

Beyond the potential loss of Social Security numbers, names, addresses and credit card information, victims of health care data breaches also risk much more worrisome losses, experts said.

If health records are altered or in some way compromised in a data breach, doctors might lose critical information about a patient’s medications or health history. And that could lead to medical errors or decisions that compromise care and endanger a patient.

“Stolen health data can lead to deadly outcomes,” Belov said.

That’s why many hospitals and doctors offices end up paying a ransom to get data back from hackers. Health care organizations often won’t talk about hacks. They worry that would make them look vulnerable and expose them to additional problems.

But a cybersecurity expert with the American Hospital Association has estimated that at least a third of the time, hospitals end up paying a ransom to get information back. Unlike other industries that might be able to wait out criminals or rebuild databases, they need the information right away and can’t risk waiting.

“Patient lives are on the line when something critical happens,” said Alexander Boyd, a data privacy and security lawyer with the Polsinelli law firm.

Clients across industries regularly consult him about situations in which data has been compromised. And, among those cases, ransomware attacks happen “more often than we’d like.”

In those cases, criminals break into a company, encrypt the data and demand a payment to unlock it. When one of those attacks happens to a health care provider, it can be an emergency.

“It’s not just a money issue, it’s a well-being issue,” Boyd said. “If the health care provider doesn’t have good backups, sometimes the only option is to pay the ransom.”

Coveware, a company that helps clients respond to cyber extortion incidents, reports the average ransom payment made by victims of cyberattacks has been falling. In the third quarter of this year, the average ransom payment for all industries was $376.94, a 66% drop from the previous quarter. The median payment was $140,000, down 65%.

Boyd said companies are getting better at avoiding attacks in the first place. More often they have data backed up so they don’t have to make ransom payments.

But when a client does have to negotiate with a hacker, Boyd turns to Coveware or another firm that specializes in dealing with the criminals. Those firms know through experience how much the hackers may be willing to negotiate and whether they may actually turn over an encryption key if their demands are met.

Typically, after coming to an agreement — after, perhaps, sending sample files to verify that the hackers actually can unlock them — clients pay the bitcoin ransom (there is no escrow) and then wait for the encryption key.

None of it is comfortable.

“You hope and wait,” Boyd said.

This article first appeared on Beacon: Kansas City and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.