The nation’s cattle inventory is at its lowest level in decades, the result of a long-term decline that has been pushed even lower in recent years by drought.

Much of the country endured severe dry spells in recent years, most notably in 2022. But the impact has been especially felt in the regions where America’s beef industry is most concentrated.

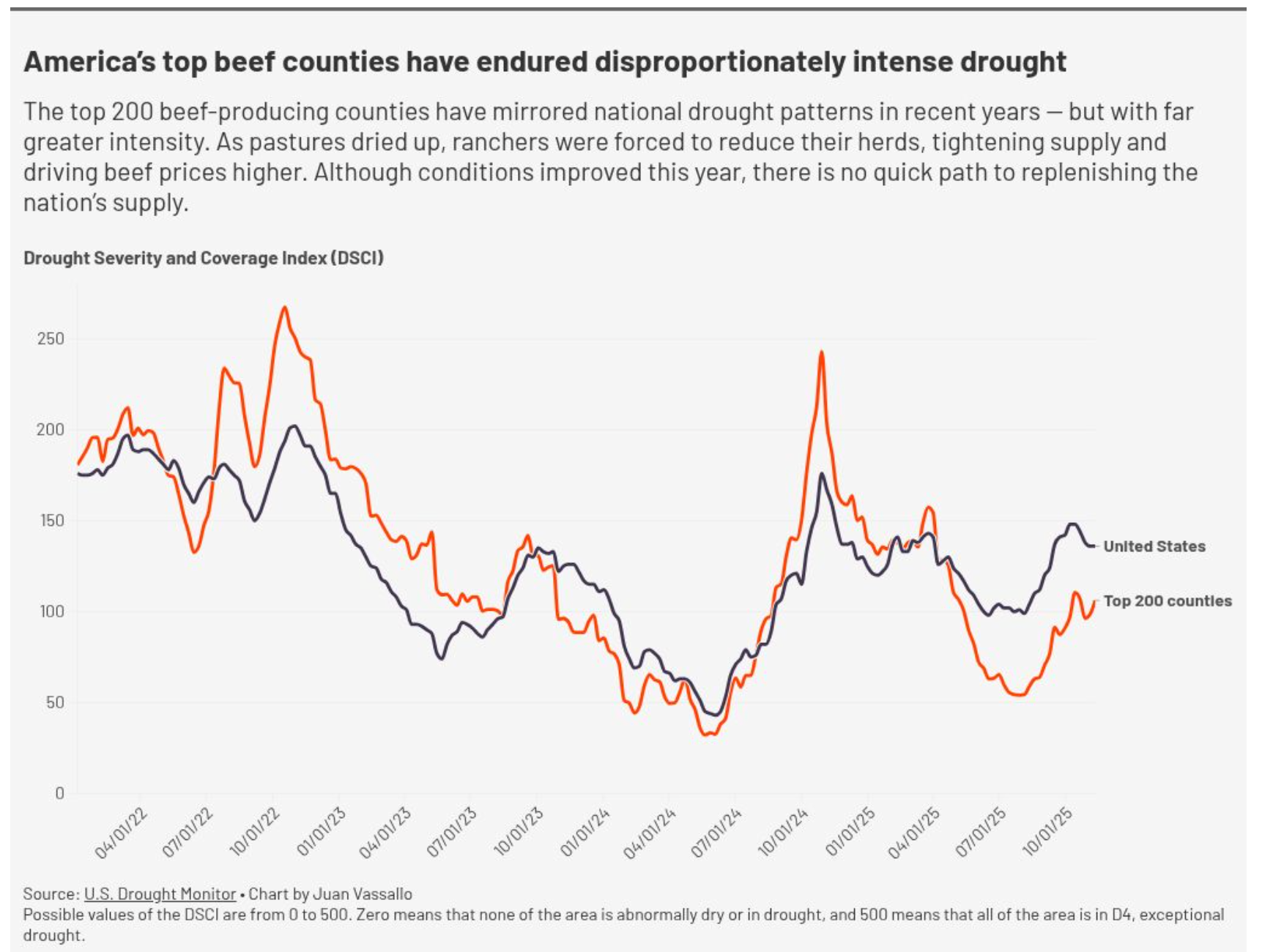

In November 2022, the U.S reached a drought index of 202 on the Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI), where values range from 0, meaning no dryness, to 500, indicating exceptional drought across an entire area. That month marked the nation’s second-highest drought reading of the century, surpassed only by the 2012-2013 North American drought.

But for the top 200 cattle-producing counties — together representing roughly a quarter of the national herd — the drought index peaked at 267.5 in the same period, far higher than the national average.

A similar pattern happened in 2024, when national drought conditions intensified in October and November, and again were more severe across the top beef-producing counties. These counties span 21 states. While they are largely clustered across the central U.S. — particularly in the top five beef-producing states of Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Nebraska and South Dakota — several are outside that core region as well, including in states like Oregon and Florida.

Ranchers in those regions have faced shrinking pastures, dwindling water supplies and the rising cost of feed, conditions that have forced many to thin their herds. And because rebuilding cattle numbers is a slow biological process, there is no quick path to replenishing the nation’s supply.

As beef prices continue to rise, meat has become a political flashpoint.

The Trump administration has ordered a review of consolidation in the meatpacking industry and lifted tariffs on beef imports from Brazil and Argentina in an effort to expand supply, while also blaming immigrants and former President Biden for the high cost of beef.

But experts say the price surge is mostly driven by drought, which has shown signs of improvement in recent months.

This year, the top 200 beef-producing counties have fared better than the rest of the country.

“Drought conditions have improved to the point where it is not a major limiting factor for potential herd rebuilding,” said Derrell Peel, professor of agricultural economics at Oklahoma State University and one of the country’s leading experts on the cattle industry. “Drought is less of an issue now compared to the last several years.”

This article first appeared on Investigate Midwest and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.